Context

MSc Group Project – University of York

Role

UX Researcher

Duration & Date

3 months, Winter 2019

Collaborated with

Kiana Zandi

Ryan Southall

Liyao Dong

Summary

This project was completed as part of coursework for my MSc in Human-Computer Interaction. We studied how a more specific warning label for ‘Loot Boxes’ affected parent’s perceptions of video games. We used both a quantitative and qualitative survey to gather data from 49 parents who have children that play video games.

We found that parents were less likely to agree with buying their child a game, or letting their child play a game, if labelled with ‘Loot Boxes’ as opposed to ‘In-Game Purchases’. Qualitative data suggests a wide variety of understanding and opinions on the term ‘Loot Boxes’. This suggests that current labelling by agencies such as the ESRB and PEGI aren’t providing enough information to parents to make fully informed decisions.

I collaborated with Liyao Dong, Ryan Southall, and Kiana Zandi on this project. We collaborated on all sections; I was particularly involved in designing the survey in Qualtrics and analyzing the quantitative data with R.

Brief introduction

Loot boxes are a form of microtransaction (a small, in-game purchase) within video games that players can purchase with real money, and offer randomised rewards. They play an increasingly important role in monetizing video games, and many publishers have adopted them as their primary method for generating income.

Unfortunately, loot boxes have repeatedly been shown to be linked to problematic gambling behavior – there is a correlation between the use of loot boxes and gambling in a ‘negative’ way.

Even worse, research shows that many video games designed for children feature loot boxes, and there is a large amount of evidence that children use loot boxes.

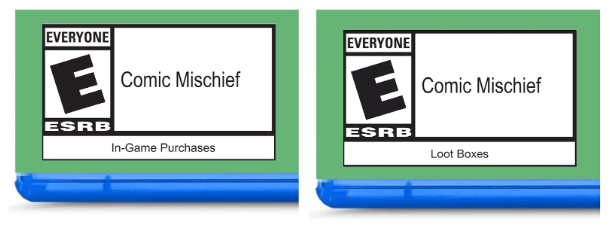

As a result, we investigated whether warning labels that specified if a game contains ‘loot boxes’, as opposed to just ‘in-game purchases’ changed how parents perceived a video game

Method

We opted to do an online survey, as we could get information from a larger and more diverse sample.

Participants

- For the purposes of our study, we only wanted responses from parents who currently have children (aged 3-17) that play video games.

- We received 193 responses, of which only 47 were fully eligible.

- We recruited participants via online forums.

Survey

- First we collected consent and demographic data from participants, determining eligibility.

- Next, they were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Each condition saw only one of the labels.

- Next we asked parents to rate the following on a 1-5 Likert scale. We also asked participants to give a written reason for the rating:

- I would buy this game for my child.

- I would let my child play this game.

- I would let my child use real money to make purchases within this game.

- We asked parents to define a loot box for us to test their understanding.

- Finally, we debriefed them on the research and provided a way for them to contact us.

Results

Quantitative

Hypothesis:

For all 3 Likert items, where β is the regression coefficient:

H0: β (Loot Boxes) = 0

H1: β (Loot Boxes) ≠ 0

A linear regression model was chosen to analyse the quantitative results. It was chosen as we wanted to include a mix of continuous (Parent Age, Youngest Child) and categorical variables (Condition, Parent Gender, and Parent Gamer) in the analysis. We decided to select 4 additional variables based on what we thought might affect agreement.

We tested for violations of the assumptions of linear regression, with none found.

Table 2. I would buy this game for my child.

Linear Regression

| Condition | Estimate (β) | Std. Error | t value | p-value |

| Condition (loot boxes) | -1.32 | 0.36 | -3.68 | <0.01*** |

| Parent Age | -0.01 | 0.03 | -0.24 | 0.81 |

| Parent Gender (Male) | 0.96 | 0.45 | 2.12 | 0.04* |

| Parent Gamer (True) | -0.23 | 0.63 | -0.36 | 0.72 |

| Youngest Child | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.37 | 0.18 |

Significance. codes: (0‘***), (0.001 **), (0.01 *)

Multiple R2: 0.35, Adjusted R2: 0.27

F-statistic: 4.40 on 5 and 41 DF, p-value: <0.01

Table 3. I would let my child play this game.

Linear Regression

| Condition | Estimate(β) | Std. Error | t value | p-value |

| Condition (loot boxes) | -0.83 | 0.36 | -2.30 | 0.03* |

| Parent Age | -0.02 | 0.03 | -0.95 | 0.35 |

| Parent Gender (Male) | 0.52 | 0.45 | 1.15 | 0.26 |

| Parent Gamer (True) | 0.11 | 0.63 | 0.18 | 0.86 |

| Youngest Child | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.62 | 0.11 |

Significance. codes: (0‘***), (0.001 **), (0.01 *)

Multiple R2: 0.20, Adjusted R2: 0.10

F-statistic: 1.99 on 5 and 41 DF, p-value: 0.10

Table 4. I would let my child use real money to make purchases within this game.

Linear Regression

| Condition | Estimate (β) | Std. Error | t value | p-value |

| Condition (loot boxes) | -0.09 | 0.31 | -0.30 | 0.76 |

| Parent Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.86 |

| Parent Gender (Male) | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.65 |

| Parent Gamer (True) | 0.82 | 0.57 | 1.44 | 0.16 |

| Youngest Child | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.30 | 0.03* |

Significance. codes: (0‘***), (0.001 **), (0.01 *)

Multiple R2: 0.23, Adjusted R2: 0.13

F-statistic: 1.99 on 5 and 41 DF, p-value: 0.056

Qualitative

We analyzed the qualitative data using a two-step process of first open coding, then thematic analysis. The qualitative data was an important step in making sense of the quantitative results we had collected. The final inter-coder reliability was high at 0.88. The themes that emerged were:

- In-Game Purchases

- Lack of Information

- Parental Role

- Rating

- Gambling

The main findings from the qualitative data were that:

- The majority, but not all parents had a reasonable understanding of what a loot box is.

- Many parents explicitly objected to their child playing a game if it contains loot boxes.

- Some parents explicitly thought of loot boxes as a form of gambling, without being prompted.

- Overall, parents are generally concerned about the possibility of their children making in game purchases

Conclusion and Discussion

- The significant differences for “ I would let my child buy this game” and “I would let my child play this game” suggests that parents would behave differently if games had more precise labelling.

- Our study confirmed that some parents have no concept of what loot boxes are. This is important, as it implies parents have insufficient information to make informed choices about what games their children play.

- However, we should treat results cautiously as our final participant count was n=47.